The post below was originally given as a paper entitled ‘”Within this music’s darkness are glinting the treasures”: Four Theses on Weird Metal’ at The Weird: Fugitive Fictions and Hybrid Genres – a conference run by the University of London on 8 November 2013. It has been tweaked to make sense as a blog post, with recent additions added in square brackets.

I intend to further develop the theses I offer here on Weird Metal Blog in the future, as well as the short case studies into Portal and The Great Old Ones. I’d be very interested in discussing some of these points with anyone who’s interested.

*

This post is concerned with the following question: how does music from the sub- category of heavy metal known as ‘extreme’ metal pertain to The Weird?

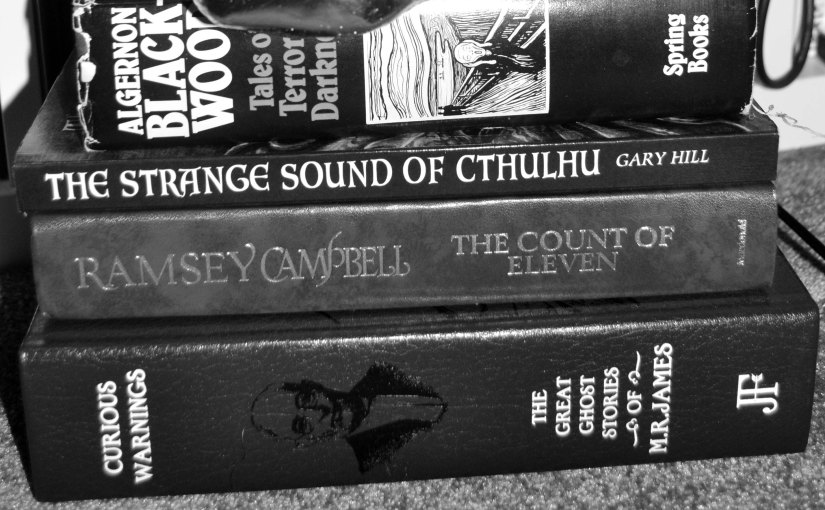

In music generally it seems to be Lovecraft, of all the classic Weird writers – as is the case in other media – who has had the most influence: in The Strange Sound of Cthulhu (2006), Gary Hill explores Lovecraft’s impact upon genres as varied as electronica, Classical, “psychobilly”, surf, and ambient, but devotes the most pages to heavy metal. Keith Kahn-Harris, amongst others, has further qualified this point, identifying extreme metal as the locus of Lovecraft’s influence (41; Smith 153-154; Baddeley 264; Hill 43; Collins 61).Like ‘The Weird’ in relation to literature, ‘extreme metal’ is often used as a catch-all, umbrella term for metal that displays qualities deemed esoteric, macabre, or otherwise socially and sonically unacceptable. In some ways, I wish to argue, extreme metal – especially the subgenres black, death, and doom metal – can be distinguished from traditional heavy metal by a fundamental predisposition for aspects of The Weird.

As critical attention on The Weird gains momentum, exemplified by the recent conference Weird Council on the work of China Miéville [14-15 September 2012], a similar increase in attention is being paid to extreme metal, especially to the sub-genre of black metal, exemplified the publication of critical and theoretical texts on the subject since 2006, and the ‘Black Metal Theory Symposium’ held in Brooklyn in 2009, and Dublin in 2011.

Over 120 extreme metal acts worldwide directly reference Lovecraft, most obviously through their choice of moniker, including: Azathoth from Slovakia; Cthulhu and Shoggoth, both from Mexico; Innzmouth from Syria; and Yog Sothoth from the U.S. While some acts describe their music as ‘Lovecraftian’ – such as Black Blood from

India, Perpetuum from Chile, Portal from Australia – neither musicians nor critics, to my knowledge, have yet considered what the category of ‘Weird Metal’ might entail. [Some artists mentioned above appear to have hung up their leathers since I gave this paper.]

I am interested in more superficial Weird references, but here I briefly outline four theses that explore deeper philosophical, ideological, and aesthetic, parallels between The Weird and Extreme metal, arguing that extreme metal is certainly the dominant site for manifestations of the ‘Weird’ in metal, maybe even in popular music generally.

1. Hybridity

As China Miéville states, “Weird Fiction is usually, roughly, conceived of as a […] generically slippery macabre fiction”: a hybrid form constituting elements of horror, fantasy, and science fiction (509). In my view, genre hybridity, too, is a prominent feature of many extreme metal acts, whether they acknowledge it or not. Some acts, especially black metallers, pride themselves on the alleged purity of their sound, trying to capture the fundamental essence of the genre, outlawing all extra-generic elements. In their purest forms, the three key sub- genres are as follows:

Black Metal features screamed or shrieked vocals, “tremolo”(quickly and regularly) picked guitar harmonies, frequently very dissonant, featuring the harmonic minor scale; aggressive ‘blastbeat’ drums; lyrics about Occultism, blasphemy, and war; and deliberately abrasive-sounding “low-fi” recordings.

Death Metal is characterised by much “heavier” guitars – down-tuned and thick-toned – low, guttural “demonic” vocals, songs structured by intense clusters of fast (between 180 – 240 bpm) complex riffs often using atonality and chromaticism; lyrics depict extreme scenarios of abjection and body horror; and recordings achieve a “thick wall” of distorted sound.

Doom Metal also features heavy guitars, playing more minor keys, is very slow (often around 30 bpm), which Ronald Bogue identifies as Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘cosmic time’: ‘the time of the Aeon […] non-pulsed rhythmic time of irregular, incommensurable intervals’ (103); accompanied by melancholic wailing/moaning vocals singing about grief, woe, and existential terror.

Hybrid strains, however, proliferate. Death and doom may be ‘blackened’, such as Canada’s Woods of Ypres, where the guitar tone and speed frequently indicate doom, but the vocals are higher, and screamed rather than growled; death collides with doom in Bradford’s My Dying Bride, amongst others, blending low demonic death vocals with the grief-laden, melancholic timbre of doom, played to a startling mixture of cosmic time and hyperspeed. Even projects usually considered separate from extreme metal, such as electronica for instance, can still be considered similarly ‘extreme’ for their integration of such elements, leading to hybrid styles such as ‘dark electro’, ‘aggrotech’, or ‘hellectro’. Further extreme metal strain, grindcore, combines all unpleasant sonic elements: extreme metal, industrial, noise, and “gabber”, (extreme techno).

Furthermore, as in many genres, the prefix ‘post-’ is used in extreme metal – post- black metal, post-doom, etc. – indicating the reinvention or reinterpretation of the described genre, the prominent incorporation of unusual extra-generic tropes into a sound that still maintains the essence of the original genre, and/or an alternate approach to composition that moves away from traditional verse-chorus structures, instead relying on transition through various moods and timbres, where passages segue fluidly. Post-black metal, for example, such as that played by the heavily Lovecraft-inspired French band The Great Old Ones, draws upon techniques of ambient music to create harsh soundscapes in cosmic time, but without the thickness of guitar tone necessary to be considered as doom.

Genre hybridity, then, is one way that metal becomes Weird, endlessly shaping itself into even stranger forms. Certain aesthetic qualities of black metal in particular, however, can be understood as evoking different aspects of The Weird through their reaching towards what I call:

2. The Black/Weird Sublime

If, as Miéville argues, The Weird “punctures the supposed membrane separating off the sublime”, allowing “swillage of that awe and horror ‘from beyond’ back into the everyday” – a “radicalized sublime backwash” (509) – then certain strains of extreme metal seek to reproduce that backwash in sonic form. Miéville explains that this horror is to be found nestling in angles, bushes, and strange limbs, but also, crucially, in noises, echoing the assertions of the great utopian thinker Ernst Bloch that music has the “capacity to transcend the utterable” through “its nonverbal, nonrepresentational, abstract character” (Levitas, 221).

This reaching toward the sublime, present in aspects of Occultism and Gnosticism, holds a similar fascination for extreme metallers as it did for Weird writers like Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood, with some musicians arguing for their performances as ritualistic or transcendental practice. The title of a controversial essay ‘Transcendental Black Metal’, written by Liturgy frontman Hunter Hunt-Hendrix, refers to the emergent ‘truly American Black Metal’ that he argues challenges traditional ‘Hyperborean Black Metal’ from Scandinavia, in accordance with his somewhat radical re-conception of heavy metal history (54).

Extreme metal is generally understood as one outcome of a “chance series of stylistic shifts”: in the late-1970s rock became ‘harder’, becoming heavy metal in the 80s; later that decade becoming thrash; in the 90s, death, which eventually proliferated, and sub-divided. To Hunt-Hendrix, however, the genre’s history displays an ever-increasing level of intensity: a slow but inexorable move towards “a hypothetical total or maximal level of intensity […] the horizon of heavy metal” that he calls the Haptic Void (55).

Deleuze and Guattari defined music as the “creative, active operation that consists in deterritorializing the refrain” (101); the Haptic Void, then – white noise, maxim sonic intensity – is the “deterritorialization of all musical components at the same time”, leading “only to […] chaos” (101). Speaking about music is inevitably an act of synaesthesia: comparing theory of black metal and the sublime often conflates extreme sound with extreme light, as in Edmund Burke’s conception of the Sublime: ‘extreme light, by overcoming the organs of sight, obliterates all objects, so as in its effects exactly to resemble darkness’ (Shaw, 67): white noise, black metal. Listening to the latter is to hear a churning maelstrom of extreme sound that almost overcomes hearing, seems paradoxically to obliterate sound altogether, striving to access the pure, sublime ‘blackness’ of the void (Airaksinen, 13).

Just as the haunted protagonist of Lovecraft’s 1921 short story ‘The Music of Erich Zahn’ yearns ‘to fill the void with music […] to distinguish himself from the nothingness’, Weird Metal seeks to fill the music with the void – striving to achieve maximum intensity – perhaps giving its listeners a glimpse into the nothingness of the void (Airaksinen 13).

3. New Weird Metal

So Hunt-Hendrix’s ‘Transcendental Black Metal’ proposes not only a re-conceptualisation of metal history, but a radical political, aesthetic, and ideological conception of black metal (54): if New Weird aims to be fiercely progressive in literary and political terms, then similarly, according to, Hunt-Hendrix, Transcendental Black Metal is a “reanimation of the form of black metal with a new soul” (59). If Miéville, Steph Swainston et al revise the antiquated or reactionary attitudes of some classic Weird authors, new forms of black metal turn the ‘chaos’ and ‘frenzy’ (his terms) of their music away from nihilism, towards affirmation and ‘ecstasy’ (59).

The U.S. post-, or ‘transcendental’, black metal artists Wolves in the Throne Room have received most attention in this regard, more so (ironically) than Hunt-Hendrix’s own band Liturgy, for the concept of ‘deep ecology’ that pervades their music and lifestyle, and their explicit rejection of traditional black metal’s often Satanic, anti-religious ideologies. Living in a self-maintained farm outside Olympia, the duo eschews many of the comforts of modernity, uses strictly vintage musical equipment, and frequently performs outdoors.

While the lyrics and music of Wolves in the Throne Room direct aggression at modernity’s transformation of the natural world, perceived as cold and synthetic, they also express awe at the magical, sublime qualities of the natural world in a manner strongly reminiscent of the practices and fiction of Algernon Blackwood. A mystic and Occultist, Blackwood, believed – like Wolves – that he was “possessed by nature”, which at its peak meant that “the ordinary world […] fell away like so much dust” (The Magic Mirror, 8).

He travelled extensively, regularly sleeping outdoors: “Here I lay and communed,” he states in a diary entry, “there were no signs of men, no sounds of human life…nothing but […] a sort of earth-murmur under the trees… as the material world faded away among the shadows, I felt dimly the real spiritual world behind shining through” (8). It is easy to imagine him intoning the Wolves song: “I will lay down my bones among the rocks and roots of the deepest hollow next to the streambed/ The quiet hum of the earth’s dreaming is my new song (wittr.com).

The last next image in the song, “When I awake, the world will be born anew” (metalarchives.com), is profoundly utopian, despite somewhat paradoxically accompanying imagery of death and decay; in Ernst Bloch’s writing on the philosophy of music, however – as cryptic as it is beautiful – he in fact locates hope in music about death because of, and not instead of its subject matter, arguing that “all music of annihilation points to a core which, since its seeds have not yet blossomed, cannot decay” […] Within this music’s darkness are glinting those treasures which are safe from rust and moths” (Essays on the Philosophy of Music, 241).

He seems to see that music is eternal, prevailing beyond death, and continually just about to occur, imbued with potential; therefore, maybe ‘music of annihilation’, even black metal, reveals the principle of hope after all.

Similarly, black metal could contain the seeds of utopia. Evan Calder Williams identifies black metal’s “endless antagonism” as directed against “liberal capitalism’s eternal present” (Hideous Gnosis, 133), arguing for the genre’s apocalyptic nature, attempting to uplift the veil of the present, although he acknowledges that the genre seems hopelessly locked into a deadly cycle where the “banality and brutality of the contemporary world is both intolerable and inescapable” (135).

4. Atmosphere

As Lovecraft declared that “Atmosphere […] not action, is the great desideratum of weird fiction”, so Ronald Bogue argues for the importance of a ‘concentration on mood and atmosphere’ in extreme metal (106). On stage many extreme metallers maintain genre clichés: spiked leather, blood, hooded cowls, fire-breathing, pentagrams, etc. Many, however, create more original aesthetic spheres in their music, artwork and performances.

Wolves’s music and performances evoke the “mythic pastoral world” that they believe we crave on “a deep subconscious level” (‘Bio’, Wittr.com) both onstage and off: concerts are held in forests, surrounded by burning pyres; tracks begin with falling rain, and contrast ethereal female singers with snarling blackened vocals.

Case Study: The Great Old Ones

From an obscure corner of Bordeaux arise The Great Old Ones, atmospheric post-black metal artists that seek to recreate the atmosphere of the Cthulhu mythos, depicting Cyclopean monoliths rising from strange seas, painted in bold impressionistic strokes; violent oceanic currents interrupted by, and magnified in, undulating layers of power chords and tremolo (dis)harmony; anguished growls that declare love for the stars from a first-person narrator that can only be great Cthulhu itself; a retelling of the Biblical Jonah, swallowed not by a whale, but by tentacled star-creatures offering enlightenment to those that they temporarily ingest.

Case study: Portal

If The Great Old Ones, then, can be considered one of the most Lovecraftian of acts – both through explicit reference and overall aesthetics – I would like to discuss Australia’s Portal as truly Weird Metal.

Renowned for bizarre stage costumes, where the band’s singer The Curator frequently appears in a shrouded cloak, adorned with Lovecraftian tentacles, their lyrics like Burroughs or Beckett at their most obscure, and their hybridised sound, often (channeling Lovecraft) labelled “indescribable” – Portal are undoubtedly a singular musical entity.

Across four albums, the band is steeped in the imagery of horror and science fiction, especially Lovecraft; but also – more uniquely – German Expressionism and 17th Century clocks. Portal’s name was chosen, according to their lead guitarist, who goes by the stage name Horror Illogium, “due to unfathomable imaginings of horrible evil seeping into this dimension, that which we have opened, that which we are” (Voices from the Dark Side).

I think that, by their elaborate commitment to such a uniquely bizarre aesthetic, their re-conceptualised, hybridised sound, and their attempt to embody the output of regions beyond the sublime, Portal should be considered as quintessential Weird Metal.

Conclusion: the weird and ‘The Weird’

As a musical form made by outsiders for outsiders, concerned with esoteric topics, and composed of sonic elements deemed unacceptable by conservative listeners, metal has always been, in the mundane sense, weird. Since its inception, heavy metal musicians have augmented their songs with references to a huge variety of mythic and mythopoeia systems and fantastical genres; there is no surprise, therefore, that in the murky, extreme backwaters of the genre, metal dovetailed with The Weird.

To me, extreme metal is where musicians have made the most concerted and successful attempts to convey the tone, affects, philosophy and themes of Lovecraft and other Weird writers, rather than drawing upon them in a humorous, parodic or otherwise incongruous manner. While certainly not all extreme metal directly pertains to The Weird, I think there are fundamental parallels between the two forms that cannot be ignored. Through key overlaps such as the hybridization of genre, a puncturing of the sublime, the shared intentions of some practitioners to make themselves ‘new’, and the (re)creation of singularly strange atmospheres, we can start to clear space for the category of Weird Metal.

The theses I outline are just the beginning. I hope that they inspire others to consider what Weird Metal might entail, and that other myriad art-forms will continue to be ruptured by the sublime backwash of The Weird.

Works Cited

- Ashley, Mike, ed., The Magic Mirror: Lost Supernatural and Mystery Stories (Equation, 1989).

-

Baddeley, Gavin and Filth, Dani, The Gospel of Filth: a Bible of Decadence and Darkness (Surrey, Fab Press, ltd, 2009).

- Bloch, Ernst, Essays on the Philosophy of Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

- Bogue, Ronald, ‘Violence in Three Shades of Metal: Death, Doom and Black’, in Deleuze’s Way: Essays in Transverse Ethics and Aesthetics (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2012) 35-52.

- Campbell, Jason, ‘Interview with Portal’, the Voices from the Dark Side website, http://www.voicesfromthedarkside.de/Interviews/PORTAL–7050.html (Accessed: 9/02/16).

-

Collins, Simon, ‘Bong: Beyond Ancient Space’, Terrorizer, Issue 211, 61; July 2011, final ed.

- Hill, Gary, The Strange Sound of Cthulhu (lulu.com, 2006).

- Hendrix, Hunter Hunt, ‘Transcendental Black Metal’, in Masciandro, Nicola, Shakespeare, Stephen, eds., Hideous Gnosis: Black Metal Theory Symposium Vol 1 (Createspace, 2010).

-

Kahn-Harris, Keith, Extreme Metal: Music and Culture on the Edge (Oxford: Berg publishers, 2007).

- Levitas, Ruth, ‘In eine bess’re Welt entrückt: Reflections on Music and Utopia’, Utopian Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2010.

- Miéville, China, ‘Weird Fiction’, in The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction, eds., Mark Bould, et al (London: Routledge, 2009) 510-515.

- ‘Portal (Australian band)’, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portal_%28Australian_band%29 (Accessed: 9/2/16).

- Shaw, Philip, Sublime (London: Routledge, 2005).

- Wolves in the Throne Room, ‘Bio’, http://wittr.com/bio/ (Accessed: 9/02/16).

- Wolves in the Throne Room, “I Will Lay Down My Bones Amongst The Rocks And Roots”, Two Hunters, http://www.metal-archives.com/albums/Wolves_in_the_Throne_Room/Two_Hunters/529724Metalarchives.com (Accessed: 9/02/16).